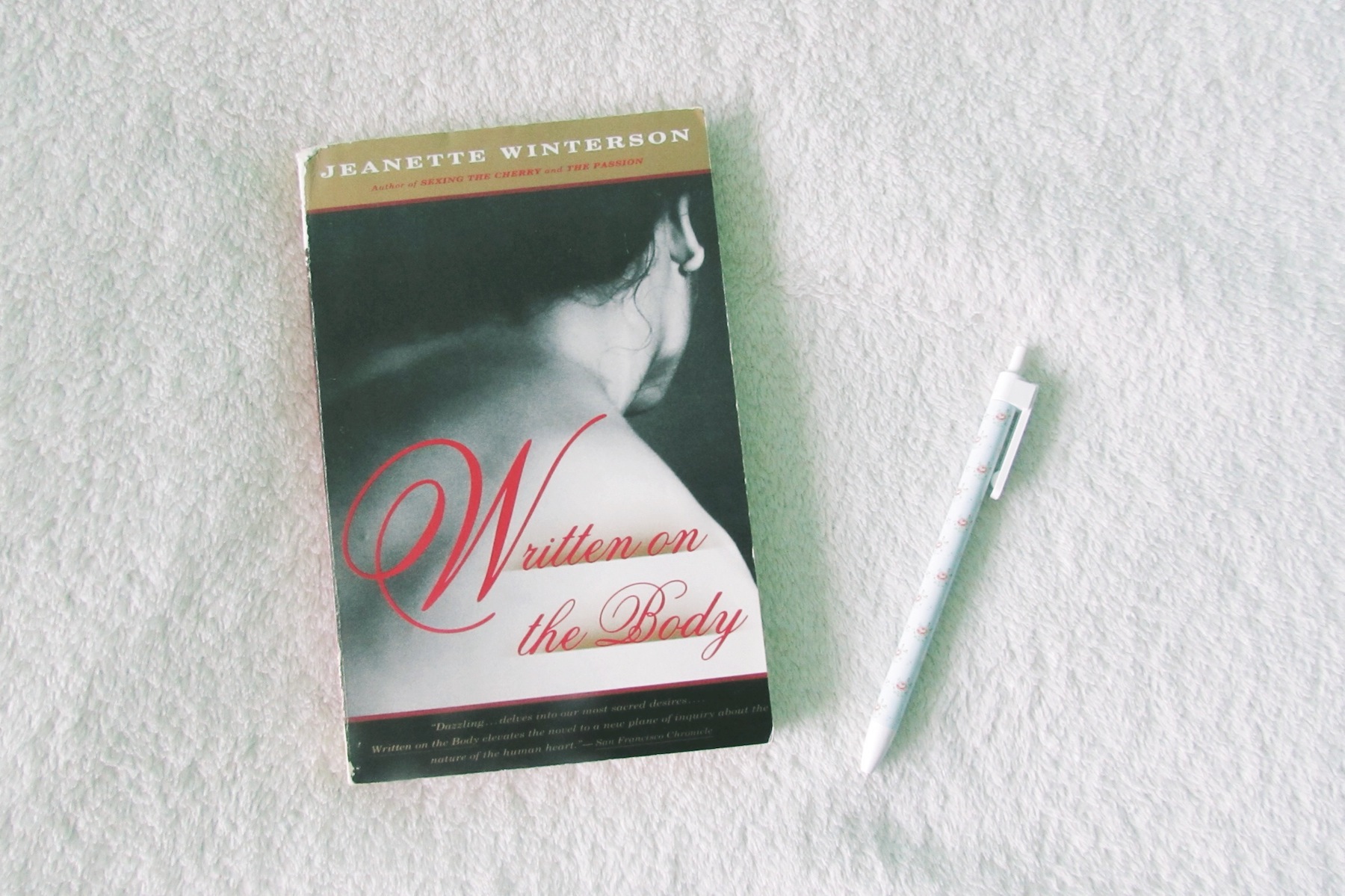

Written on the Body by Jeanette Winterson (1994)

ISBN: 9780679744474

So, I recently finished Written on the Body by Jeanette Winterson. When I made my previous post about the opening lines of the novel, I had just begun rereading the book. I originally had to read it for my Contemporary British Novels class when I was in university and well, I read it but didn’t read it. You know what I mean right? When you read books for class, there’s almost always a time constraint and you never get to read them like you normally would a book you read on your own time. But I remembered Winterson’s writing style and how the book was so beautifully written that I wanted to reread it and take it all in like I would a book that I would pick up and read on my own.

It’s a beautiful read. The pose is very poetic and if you don’t like that type of poetic prose, then this book may not be for you, because the entire book is written like that. But Winterson is so clever and she makes references to lots of classic literary works from Shakespeare to Melville. The book is smart and even though it chronicles the narrator’s romance with Louise, it’s not your typical romance novel. For one, it’s more of an exploration of love and what love is. In that sense, the novel’s quite philosophical as well. Secondly, the narrator has no distinct gender. We, as the reader, never know whether the narrator is male or female because the narrator talks about having both boyfriends and girlfriends. Yet, this lack of gender of the narrator only enhances one of Winterson’s points about love.

And Winterson makes many points about love. The first being that love is measured by loss, or the loss of said love. Another reoccurring point–and a really important one at that–she makes is “it’s the clichés that cause the trouble.” In that, society has a certain romanticized view of what love should be and how both partners should act when in love, yet it’s all so common and unrealistic because no love is like that. Love is a lot more complicated than the clichés. Take one of my favorite passages for instance:

“You said, ‘I love you.’ Why is it that the most unoriginal thing we can say to one another is still the thing we long to hear? ‘I love you’ is always a quotation. You did not say it first and neither did I, yet when you say it and when I say it we speak like savages who have found three words and worship them. I did worship them but now I am alone on a rock hewn out of my own body.”

And another:

“You’ll get over it…” It’s the clichés that cause the trouble. To lose someone you love is to alter your life for ever. You don’t get over it because ‘it’ is the person you loved. The pain stops, there are new people, but the gap never loses. How could it? The particularness of someone who mattered enough to grieve over is not made anodyne by death. This hole in my heart is in the shape of you and no-one else can fit it. Why would I want them to?”

Winterson’s narrator questions love, yet always seems to answer them with not definitive answers, but answers that leave room for more thought and questioning. It’s really a lovely read, and while the end could drag on a bit, it’s still really good and I recommend it to everyone.